April 2023

Article

5 minutes

Scottish Mortgage: looking beyond tough times to future opportunities

Tom Slater – Manager, Scottish Mortgage

Key Points

- Scottish Mortgage has weathered occasional tough times over its long history

- Backing the growth companies of tomorrow means embracing uncertainty

- Disciplined long-term investors can capture the outsized impact of a small group of transformational companies

Please remember that the value of an investment can fall and you may not get back the amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future returns. This article originally featured in Baillie Gifford’s Spring 2023 issue of Trust magazine.

The other day I bumped into a former Baillie Gifford senior partner, who had retired more than 20 years ago. As always, he questioned me closely about Scottish Mortgage.

We talked about the recent decline in its value and the challenges of the current environment. To be honest, I was fishing for confirmation that market conditions were especially tough.

I have to say, he didn’t bite. Investing during the 1970s, he told me, was far worse.

Going back to the figures, I saw he was right. That decade saw a 68 per cent decline in the value of Scottish Mortgage’s portfolio. During the Great Depression, there was a 78 per cent loss.

The recent 52 per cent fall in asset value doesn’t even make the top five Scottish Mortgage setbacks. This got me thinking about the lessons of the Trust’s 114-year history.

Scottish Mortgage was born out of the financial panic of 1907. One side effect of the crisis was that rubber producers in Malaya struggled to raise capital, despite demand for tyres from the emerging mass-market motor industry.

Originally named The Straits Mortgage and Trust Company, the Trust was created to help address this funding shortfall.

The planters’ problem that Colonel Baillie and Mr Gifford set out to alleviate is a good example of how little capital markets cycles have to do with the prospects of underlying technologies.

Long-term thinking

In truth, most investors aren’t interested in financing the development of long-term growth companies. Hedge funds may spring to mind here, but we should also be tough on our own asset management industry.

For business purposes, it has redefined ‘risk’ as volatility around an index, not the provision of growth capital for projects with uncertain payoffs.

But if society directs so little of its savings into exploring new technologies and ways of doing things, what does that imply for the future? Without investment in new technologies and infrastructure, it will be tough to improve living standards.

New technologies and better ways of doing things are rarely adopted simply because ‘their time has come’. They happen because investors have used their capital to give entrepreneurs time and space to turn vision into reality.

Let’s take a current example, electric vehicles (EVs). Consumers have shown a clear preference for faster, safer and cheaper EVs.

Manufacturers are selling all they can produce, and everyone is scrabbling around to secure supplies of components. But there is a significant capital cost associated with this green transition.

The need to find ways to supply risk capital to fund EV development is one reason Scottish Mortgage invests in the battery maker Northvolt.

Even with a highly experienced management team and access to cheap power in northern Sweden, it has not been easy for the company.

That is partly because the venture capital industry has got too used to capital-light online business models. The idea of deploying billions of dollars to build physical capacity in northern Europe is anathema to many. To me, it’s the proper job of the long-term growth investor.

Hold discipline

When Scottish Mortgage takes shares in these companies on your behalf, it takes a share in their success or failure over the coming years and decades.

This long-termism is profoundly unfashionable. In these uncertain times, investors are busily selling stocks in higher-risk companies rather than trusting business founders and leaders to get on with the job of navigating a challenging environment.

What’s worse, investors dignify that with the term ‘sell discipline’. I’m always puzzled how staying invested in a company you believe in is seen as ill-disciplined or lazy. I believe the opposite is true. To take advantage of an opportunity, you need ‘hold discipline’: the resilience to hold these companies through difficult times.

Take Amazon. We first bought the company in 2004. By 2006, its share price had fallen by a third. Its management was being pilloried for launching a subscription service that offered free delivery, turning its most regular customers into its biggest loss-makers. The market hated how that hit profitability forecasts.

But that step towards launching Amazon Prime arguably underpinned the firm’s rise to becoming one of the world’s biggest retailers. The market hates uncertainty, but uncertainty is inevitable with risky projects that can have big payoffs. I share the view of the celebrated US investor Shelby Cullom Davis: “You make most of your money in a bear market. You just don’t realise it at the time.”

The real test of being a disciplined long-term investor isn’t when you decide to sell something. It’s how you endure the periods when everyone thinks you’re wrong to stick with a stock. Despite all the stress of a market downturn, this might be when the underpinnings of growth are established.

Unequal performance

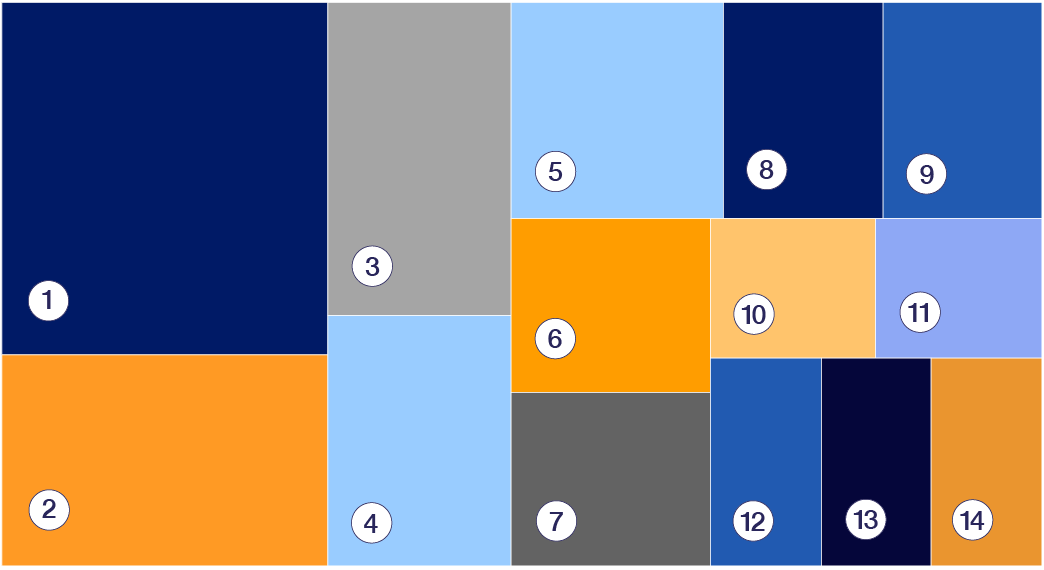

What matters most is capturing the outsized impact that a small group of companies can have. We don’t have the data for the past 114 years, but for the past 20 Scottish Mortgage has tracked the contribution of individual holdings.

Over those two decades, we’ve owned 749 stocks and bonds. Of those, 680 – about 91 per cent – have made zero net contribution to the overall return.

The roughly 12-times return we achieved over the period was driven entirely by 69 assets – just 9 per cent of the holdings. Indeed, half of that growth came from just 14 investments. (see graphic)

So great is the disconnect between financial markets and the companies that create wealth that I tend not to comment about interest rates, GDP growth, or whether there will be a recession. I have my views, but they don’t matter much to my job.

The 14 assets that have earned half of Scottish Mortgage’s 12-times return on investment

| 1 | Amazon | 10% |

| 2 | Altas Copco | 6% |

| 3 | Petrobras | 5% |

| 4 | Tencent | 4% |

| 5 | Baidu | 4% |

| 6 | Brazilian inflation-linked bond* | 3% |

| 7 | Tesla | 3% |

| 8 | British American Tobacco | 3% |

| 9 | Vale | 3% |

| 10 | Kering | 2% |

| 11 | Barclays | 2% |

| 12 | Illumina | 2% |

| 13 | Alibaba | 2% |

| 14 | Suncor | 2% |

Source: Baillie Gifford, 2 January 2003 to 30 June 2022. Totals may not sum due to rounding. *Inflation-linked bond which matures on 15/05/2045.

What matters is finding that handful of companies that can make a difference to overall returns and hanging on to them for long enough for the returns to accrue in your portfolio.

Looking at the past decade, it’s notable that the big-winner companies have been powered not by general economic expansion but by growth in the spread of technology systems, such as smartphones or by the discovery of new ways of fulfilling existing demand, such as ecommerce.

So far, these winners have come from a narrow set of industries, including media and retail.

But I’m struck by the breadth of the opportunities for further disruption in transport, healthcare, food, energy and finance.

Just as Scottish Mortgage’s original investors in 1909 looked beyond gloomy financial markets to the long-term opportunities of the motor age, we too must avoid being distracted when there’s so much potential out there.

Of course, we wouldn’t be able to be long-term at times like this without the support of you, our investors. We are very grateful for that.

Where we see opportunities, we must be steadfast. It takes patience and discipline to harness the growth of those few outlier companies. If we do, the payoffs can far outweigh the inevitable losses elsewhere.

A tide of change across the economy brings new opportunities. I know that even in turbulent times, as I write, visionary leaders are laying the foundations for the great growth companies of decades to come.

Annual past performance to 31 December each year (%)

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust | 4.6 | 24.8 | 110.5 | 10.5 | -45.7 |

Source: Morningstar, share price, total return. Net of fees.

Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

About the author - Tom Slater

Manager, Scottish Mortgage

Tom Slater is manager of Scottish Mortgage. He joined Baillie Gifford in 2000 and became a partner of the firm in 2012. Tom joined the Scottish Mortgage team as deputy manager in 2009, before assuming the role of Manager in 2015. Beyond that, he is the head of the US Equities team and a member of another long-term growth equity strategy. During his time at Baillie Gifford, Tom has also worked in the Developed Asia and UK Equity teams. Tom’s investment interest is focused on high-growth companies both in listed equity markets and as an investor in private companies. He graduated BSc in Computer Science with Mathematics from the University of Edinburgh in 2000.

Important information

This communication was produced and approved at the time stated and may not have been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of production and may not reflect current thinking.

This content does not constitute, and is not subject to the protections afforded to, independent research. Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned. The views expressed are not statements of fact and should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment.

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed on the London Stock Exchange and are not authorised or regulated by the FCA.

A Key Information Document is available by visiting our Documents page.

Any images used in this content are for illustrative purposes only.