April 2024

Article

5 minutes

Starlink: broadband from above

Jane Wakefield

Key points

- Starlink is on a mission to provide a globe-spanning internet service from orbit, using thousands of satellites

- The business is part of SpaceX, a company that plans to eventually transport humans to Mars

- It currently beams high-speed broadband to nearly 2.5 million customers across more than 70 countries

As with any investment, your capital is at risk. This article originally featured in Baillie Gifford's Spring 2024 issue of Trust magazine. Read all the articles here.

Next time you look up at the stars, you might glimpse a chain of lights moving across the night sky. If you didn’t know better, you might mistake them for a string of pearls gliding across the heavens. In fact, they are part of Starlink’s growing constellation of satellites.

This sky-borne train puts earthbound transport to shame, circling the globe in about 90 minutes. And as they do so, they bring high-speed broadband to places that otherwise lack it. Nearly 2.5 million users already subscribe – from remote homes to airlines and camper van owners – across over 70 countries and seven continents. Its goal is to make its signal available to half the world’s population this year.

Starlink is a subsidiary of SpaceX. One of the world’s largest private companies, it has pioneered the commercial space industry. As Scottish Mortgage investment specialist Claire Shaw puts it, the business aims “to rebuild the internet in space” by deploying as many as 42,000 satellites in orbit.

Although unlikely to be competitive in urban areas, satellite broadband can do a great job of filling the gaps left by traditional fixed-line or mobile networks in areas that are either too remote, too mountainous or otherwise inaccessible. Additionally, it can provide a lifeline when war or natural disasters sever regular services.

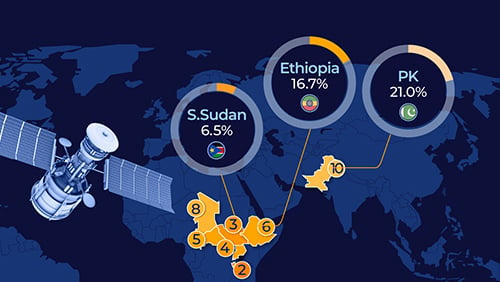

More than a third of the world’s population still lacks internet access, giving the business a huge opportunity. And a head start against a handful of other space-based internet providers makes Starlink well placed to succeed.

Co-founder and chief executive Elon Musk has suggested SpaceX will spin off Starlink with a stock market listing once it “can predict cash flow reasonably well”, but he has denied speculation that it’s working to a 2024 date. Whatever the timeline, his comments indicate that the business is capable of long-term sustainable growth as a standalone entity.

For now, there’s a benefit to being part of a larger firm. Since May 2019, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rockets have launched more than 5,500 Starlink satellites into the skies. To put that in perspective, until November 2022 the entire space industry had launched fewer than 14,500 satellites since Sputnik in 1957. Or to look at it another way, at the end of 2023 Starlink accounted for more than half of all the active satellites in orbit.

Light-weight satellites

Satellite internet dates back to the 1990s. At first, its connectivity was slow and laggy. Early devices maintained a ‘geostationary orbit’, matching the Earth’s rotation, so they appeared to hover about 22,000 miles above the ground. That distance meant data took a relatively long time to make each journey, causing an issue known as latency.

Starlink’s innovation was to put lots of lighter-weight, smaller satellites much closer to Earth, at heights of just 340 miles. It says subscribers typically get download speeds of between 25 and 220 megabits per second (Mbps), and latency is lower than on some fixed broadband connections. That’s more than adequate for a household to stream Netflix and Spotify, play the online video game Fortnite and make a Zoom call simultaneously, with bandwidth to spare.

The firm provides users with terminals. Their antennae point skywards to establish a connection with its satellites as they pass overhead. The company says the system can withstand bad weather – another problem for satellite broadband in the past – and takes only minutes to set up.

Each satellite has an operational lifespan of about five years and is designed to completely burn up on re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, leaving no debris.

“The beauty of Starlink is that it is a relatively fixed-cost business,” Shaw notes. “You know what satellites are up there, and there’s very little incremental cost to run them.” But the firm is driven by more than money, she adds. It aims to bridge the digital divide in an increasingly internet-reliant world.

“The global broadband market is a $1tn a year industry,” Shaw says. “And if Starlink can even get something like 3 per cent of that market, that’s $30bn in revenue each year.”

SpaceX’s chief operating officer, Gwynne Shotwell, is explicit about using Starlink’s revenue to help achieve Musk’s ultimate ambition of reaching Mars.

“SpaceX was created with a mission to make humanity multi-planetary. That’s at the core of the company,” says Shaw. But while it has its eyes on “the pot of gold” at the end of the Mars rainbow, it’s also laser-focused on nearer-term goals, she adds.

“When you look at what SpaceX has achieved in 10 years, it’s phenomenal. It has pretty much 80 per cent of the launch market. And it does it with reusable rockets, an extraordinary feat.”

Expanding access

SpaceX rockets aren’t just sending satellite trains into space. They also transport cargo to the International Space Station on behalf of Nasa. And in a twist, Amazon, founded by Musk’s greatest rival in the commercial space race, Jeff Bezos, has signed a contract to hitch a ride on Falcon 9 for its competing satellite service, Project Kuiper, beginning in 2025.

Starlink also recently agreed a deal with T-Mobile to help end mobile ‘dead zones’ – places without internet coverage – in the US. And in 2023, it started selling its services to customers in Chile via another Scottish Mortgage holding, the Latin American ecommerce giant MercadoLibre, as well as launching services in Nigeria and Kenya.

Starlink isn’t limited to dry land. It is working with Danish shipping giant Maersk to provide connectivity to more than 300 cargo ships, allowing their crews to make high-definition video calls to the company and their families, among other uses.

It also provides humanitarian lifelines. In February 2022, it sent about 50 Starlink terminals to Tonga following a volcanic eruption and tsunami. After the Russian invasion, at Ukraine’s request it supplied more than 20,000 terminals to plug gaps in the country’s damaged communication system.

Recently, Starlink set up a separate division – known as Starshield – specifically intended for government use to support national security efforts.

In 2017, Musk made a passionate case for humanity to have a future “out there among the stars”. Starlink may help achieve that vision, but in the meantime it has huge potential to generate value for those of us remaining earthbound.

Gwynne Shotwell: ground control to Major Musk

If Elon Musk sets SpaceX’s soaring vision, it’s the less familiar figure of Gwynne Shotwell who keeps it on trajectory. She is, according to Time magazine, “living proof that you don’t need a space suit to be a space pioneer”.

Shotwell’s importance to Starlink’s operations – including finance, customer management and government affairs – can’t be overstated.

The former Chrysler engineer has worked with Musk for more than 20 years, longer than any other senior executive. Musk’s biographer, Walter Isaacson, suggests that having a husband with Asperger’s gives Shotwell special understanding of her boss, who has also talked about having the autism-spectrum condition.

In 2008 she became president and chief operating officer after Nasa expressed concerns about Musk dividing that role with running Tesla. “I kind of need a partner,” Isaacson reports him as saying to Shotwell. “Do you want to be president of SpaceX?”

Isaacson suggests “her easy-going assertiveness allows her to speak frankly to Musk without rankling him and to push back against his excesses without nannying him”.

The writer recounts an example from 2019. Impressed by progress on the firm’s planned Starship launch vehicle, Musk ordered the existing Falcon Heavy rocket to be cancelled despite its readiness for commercial use. Panicked executives texted Shotwell, who rushed to the room to get Musk to change his mind. Without Falcon Heavy, the firm couldn’t fulfil its existing military contracts. “Once I gave Elon the context, he agreed he couldn’t do what he wanted,” as she smoothly relates it, and the Falcon Heavy continues to fly.

Course correction achieved, the two have maintained a potent partnership that continues to propel SpaceX to the stars.

Starlink’s parent company SpaceX is also held by The Monks Investment Trust, Edinburgh Worldwide Investment Trust and Baillie Gifford US Growth Trust.

About the author - Jane Wakefield

Jane Wakefield was a technology journalist for two decades, most of which was spent at the BBC. She is now a freelance writer, podcaster, conference host and media trainer.

Important information and risk factors

Scottish Mortgage has a significant investment in private companies. The Trust’s risk could be increased as these assets may be more difficult to sell, so changes in their price may be greater. Investments with exposure to overseas securities can be affected by changing stock market conditions and currency exchange rates.

The views expressed in this article should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. The article contains information and opinion on investments that does not constitute independent investment research, and is therefore not subject to the protections afforded to independent research.

Some of the views expressed are not necessarily those of Baillie Gifford. Investment markets and conditions can change rapidly, therefore the views expressed should not be taken as statements of fact nor should reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Both companies are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and are based at: Calton Square, 1 Greenside Row, Edinburgh EH1 3AN.

The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed on the London Stock Exchange and are not authorised or regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

A Key Information Document is available by visiting the Documents page at scottishmortgage.com

93113 10045464