February 2023

Article

The history of Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust

John Newlands

Summary

Launched in 1909 amid the rubber boom fuelled by soaring demand for tyres, Scottish Mortgage is now the UK’s largest investment trust. John Newlands tells its story.

© Camerique Archive/Getty Images

Please remember that the value of the investment can fall and you may not get back the amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

In December 1908, a young Scots rubber producer, Alastair Macgregor, came home on leave from Malaya with a problem. One ready to listen was the family solicitor, the 27-year-old Carlyle Gifford, younger partner in the legal firm Baillie & Gifford WS.

Macgregor described his cashflow difficulties. Land was purchased, cleared and planted with rubber trees, followed by a long wait until the sap could be tapped.

As it happened Gifford’s partner, Lt Col Augustus Baillie had been a director of the Third Mile Rubber Company since 1906. He was well aware of the City fortunes made from rubber speculation in the car boom, but The Straits Mortgage and Trust Company, launched by the legal firm’s newly created investment arm Baillie & Gifford in 1909, chose a different path.

The plan was to offer mortgages secured against the businesses themselves, a time-honoured model to which Gifford added an innovative twist: the right of conversion into ordinary shares, in other words, the lure of a share in the future prosperity of the rubber industry.

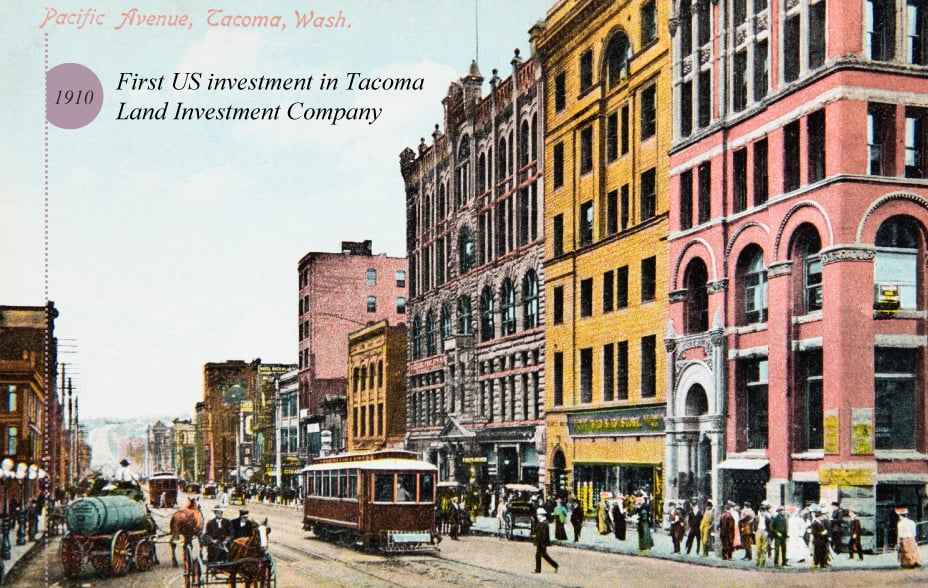

The trust’s first balance sheet produced in 1909 showed subscribed capital of just over £50,000. Gradually it acquired a broader range of holdings including The Cuban Telegraph Company, The Chilean Northern Railway and, in 1910, its first investment in the US, the Tacoma Land Investment Company of Washington State.

© This Old Postcard/Alamy Stock Photo

With diversification away from Malayan rubber came a change of name, reflecting the trust’s sturdy Edinburgh base, but a cause of confusion ever since. In 1913 the company became The Scottish Mortgage and Trust Company Limited.

For all the carnage of the First World War, the trust managed to pay dividends of between 5.5 and 6.5 per cent throughout. As the global economy recovered during the 1920s, it expanded rapidly under Gifford’s shrewd, nimble management and through a merger with another trust, Scottish Canadian. By 1925 the trust had amassed £1m in assets. That figure rose as the twenties roared to reach £4m by March 1929.

With substantial reserves built up over its first 20 years the trust came off relatively well in the Great Depression, and in the early 1930s it diversified across both fixed interest securities (48 per cent) and domestic and overseas equities. Top 10 holdings included Shell, manufacturers Turner & Newall, Calcutta Electric Supply and Margarine Unie (later Unilever).

Amid rumbles of another war, the managers presciently switched course again, coming out of Continental Europe to the US, with the percentage of European holdings dipping from 18 per cent in March 1932 to only 4 per cent by the time Hitler invaded Poland. As the war progressed, most of the trust’s dollar holdings were requisitioned by HM Government in exchange for issues of war loans. Most of the residual European holdings were worthless by 1945.

Rigorous postwar exchange controls continuing into the late 1940s meant that the trust’s portfolio was heavily skewed towards domestic securities, with an 80 per cent weighting in the UK and a mere 6 per cent in the US.

© Central Press/Getty Images

A significant return to the US in the 1950s, led by investment manager (later chairman) George Chiene, was one of the most successful moves in Scottish Mortgage’s history. Aided by borrowing, the net asset value per share multiplied more than six-fold between 1950 and 1965.

By 1969, despite Labour’s 1965 Finance Act imposing onerous capital gains tax rules on share transactions, gross assets had risen to £54 million. That year the trust merged with two other Baillie Gifford-managed trusts, Second Scottish Mortgage and Scottish Capital, taking ‘new’ Scottish Mortgage through the £100m barrier.

As the 1970s began, with UK inflation at times exceeding 20 per cent, and interest rates well into double figures, the 1973 oil crisis and a backdrop of industrial unrest amounted to “a really dreadful mess” in Chiene’s words, though North Sea oil fields helped spur recovery by the end of the decade.

The currency controls hampering overseas investment were swept away by the Thatcher government in 1979. Scottish Mortgage put this new-found freedom to good use. Within two years, exposure to US equities increased by a quarter to 40 per cent, with broadly the same in the UK and 14 per cent in Japan and the Far East.

Japan comprised 20 per cent of the portfolio by 1984 and stayed in the high teens until the end of the decade, as the ‘bubble economy’ pumped up. Along with the flourishing equity market on both sides of the Atlantic, the net asset value per share had increased by nearly 500 per cent over the 20 years to 1989, while the dividend had grown by nearly 700 per cent.

Under Max Ward, appointed lead manager of the trust in 1989, the remaining years of the century, with the exception of a modest 5 per cent decline in 1995, saw steadily rising value. A blue-chip strategy, 33 per cent weighted to the UK in 1997, made the nineties even more successful than the eighties. As former senior partner Richard Burns, author of histories of Scottish Mortgage and of Baillie Gifford wrote of Ward:

“A few of his choices were lemons [but] the vast majority were not and the overall performance of his team over the next 20 years was a key component in the success of [Baillie Gifford] as a whole.”

Total assets breached the £1bn mark in early 1993 and continued to rise as the new millennium approached.

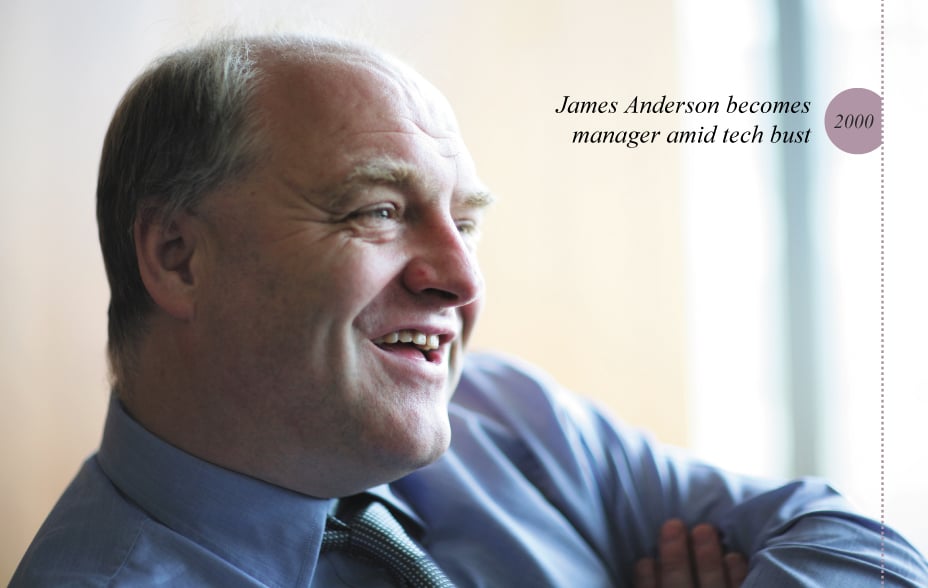

The abrupt end of the tech boom in 2000 marked the start of a painful three-year bear market in which share values fell sharply. Not the easiest moment for James Anderson, a Baillie Gifford partner since 1987, to take up the manager’s mantle in 2000.

During this testing period the chairman Sir Donald MacKay initiated a major strategic review, carried out by Anderson and the board. The conclusion? The trust should aim to maximise long-term total return from a focused, actively managed truly global portfolio. Performance would be judged over rolling five-year periods, encouraging a long-term view.

In the 10 years that followed, Scottish Mortgage would undergo radical change, coming to be dominated by Anderson’s high conviction positions in transformative, often internet- and technology-based, companies across the globe. Early examples included Amazon, Google and the latter’s giant Chinese equivalent Baidu.

This change in direction had its critics (to put it mildly). Investor Anderson was called to account, year in, year out at conferences for his “insane” early exposure to Amazon in particular. Yet history has backed his belief that his “only mistake was to sell part of the holding down too early.”

Despite its beginnings amid the most difficult market conditions for many years and encompassing the global banking crisis of 2007 to 2008 (the trust held RBS until March 2009), Anderson’s 21-year tenure, latterly in partnership with Tom Slater, has been a phenomenal success story, marked by the trust’s entry into the FTSE 100 index in March 2017. As of September 2021, the trust’s share price cumulative return from the beginning of 2000 was 2,720 per cent.

Slater, co-manager since 2015, has summed up Scottish Mortgage’s enduring purpose: “To identify the world’s most exciting growth companies and where we find them to be very long-term, supportive owners, to allow that return to accrue to our shareholders … regardless of whether a company is public or private or where it happens to be headquartered.”

This modus operandi, unencumbered by weightings and benchmarks, given powerful intellectual support by influential board members such as Professor Sir John Kay, has allowed its managers to spot and – long before the herd – invest in some extraordinarily successful companies. The trust and its shareholders reap the benefits of scale won by its success, allowing running costs to be kept low and shares to be easily bought and sold.

© REUTERS/Stephen Lam

In recent decades Scottish Mortgage shifted its focus towards what it called ‘transformational growth companies’, exemplified by Amazon (first invested 2004), Tencent (2008) and – even more controversially than Amazon – Tesla (2013). In response to changing attitudes to stock exchange listing, it led the way in investing in private companies, such as Stripe, Ginkgo Bioworks, ByteDance, Grail and SpaceX.

Another new development has been increasing stakes in carbon-reducing technologies. These have been led by the investment in Tesla, followed by companies such as battery maker Northvolt, and car-charging infrastructure company ChargePoint.

In the year to 31 March 2021, shareholders witnessed the strongest ever return produced by the company, with market capitalisation exceeding £18bn. That same month, it was announced that James Anderson would retire in April 2022, with Lawrence Burns, who has worked with Anderson and Slater for 10 years, becoming deputy. Chair of the trust Fiona McBain, credited by the managers as a rock of support in even the toughest times, summed up:

“James’s approach of identifying and holding transformational growth companies has helped drive economic progress and delivered exceptional returns for shareholders.”

The ability to envision a different future, foreshadowed by Carlyle Gifford at the dawn of the age of the motorcar, continues in Scottish Mortgage’s relentless probing for next generation growth companies. These are the ones riding – often fomenting – forces of exponential change: healthcare’s data revolution, the rise of China, the future of energy and transport. But for all the accumulated history, to Baillie Gifford’s flagship trust, in Anderson’s words, “the future matters an awful lot more than what’s happened in the past”.

Find out more about Baillie Gifford Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust

Annual Past Performance to 31 December Each Year (%)

|

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

Share Price |

4.6 |

24.8 |

110.5 |

10.5 |

-45.7 |

|

NAV |

3.9 |

26.8 |

106.5 |

13.2 |

-39.0 |

|

FTSE All-World Index |

-3.4 |

22.3 |

13.0 |

20.0 |

-7.3 |

Performance source: Morningstar, FTSE, total return in sterling.

Important Information

The views expressed should not be taken as fact and no reliance should be placed upon these when making investment decisions. They should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. If you are unsure whether an investment is right for you, please contact an authorised intermediary for advice.

This article was produced and approved in February 2023 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of recording and may not reflect current thinking.

The Trust invests in overseas securities. Changes in the rates of exchange may also cause the value of your investment (and any income it may pay) to go down or up.

The Trust invests in emerging markets where difficulties in dealing, settlement and custody could arise, resulting in a negative impact on the value of your investment.

The Trust has a significant investment in private companies. The Trust's risk could be increased as these assets may be more difficult to buy or sell, so changes in their prices may be greater.

The Trust can borrow money to make further investments (sometimes known as "gearing" or "leverage"). The risk is that when this money is repaid by the Trust, the value of the investments may not be enough to cover the borrowing and interest costs, and the Trust will make a loss. If the Trust's investments fall in value, any invested borrowings will increase the amount of this loss.

Market values for securities which have become difficult to trade may not be readily available and there can be no assurance that any value assigned to such securities will accurately reflect the price the Trust might receive upon their sale.

The Trust can make use of derivatives which may impact on its performance.

The Trust is listed on the London Stock Exchange and is not authorised or regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed on the London Stock Exchange and are not authorised or regulated by the FCA.

For a Key Information Document for the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust, please visit our website at www.bailliegifford.com

10018903 36763

About the author - John Newlands

John is a financial historian and authority on investment trusts. He was formerly head of Investment Companies Research at Brewin Dolphin. John graduated from the University of Edinburgh Business School in 1995 and has also served in the Royal Navy as a chartered electrical engineer.

Legal Notices

Source: London Stock Exchange Group plc and its group undertakings (collectively, the "LSE Group"). © LSE Group 2021. FTSE Russell is a trading name of certain of the LSE Group companies. "FTSE®" "Russell®", is/are a trade mark(s) of the relevant LSE Group companies and is/are used by any other LSE Group company under license. All rights in the FTSE Russell indexes or data vest in the relevant LSE Group company which owns the index or the data. Neither LSE Group nor its licensors accept any liability for any errors or omissions in the indexes or data and no party may rely on any indexes or data contained in this communication. No further distribution of data from the LSE Group is permitted without the relevant LSE Group company's express written consent. The LSE Group does not promote, sponsor or endorse the content of this communication.