The Firms Behind the World’s Most Critical Technology

Hamish Maxwell – Investment Specialist

- Chris Miller’s book Chip War reveals how economic, geopolitical and technological forces shape the semiconductor industry.

- TSMC has become a pivotal player, thanks to its early decision to solely make others’ chips.

- Other Scottish Mortgage holdings at the forefront include ASML and NVIDIA.

As with any investment, your capital is at risk.

In 1985, Taiwan effectively gave Morris Chang, an American businessman of Chinese birth, a blank cheque to establish the island’s semiconductor industry.

He bet on a revolutionary idea, a business dedicated to building others’ chips, not its own.

Today, Scottish Mortgage has 10 per cent of its portfolio invested in the semiconductor industry, and its holding TSMC is one of the world's most valuable firms. Several other portfolio companies, including NVIDIA, Tesla and Amazon, depend on it, while another investment, ASML, is one of its closest partners.

As part of Scottish Mortgage’s inaugural digital conference, Chris Miller spoke about the semiconductor chip industry’s development and the economic, geopolitical and technological forces that continue to shape it.

Miller is associate professor of international history at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and the author of the 2022 book Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology.

TSMC: from zero to hero

Miller describes TSMC as “indispensable and the world’s most important chipmaker”. Before its founding, it was the norm for companies to design and physically produce their own chips. The few who didn’t had to risk exposing their intellectual property to a rival.

However, Chang realised that “specialisation was key” to creating the efficiencies that would counteract the increased cost of making the ever-smaller transistors (tiny on-and-off switches) required to make more complex chips. So, he focused on pioneering the foundry – a factory dedicated to manufacturing others’ designs.

That paid off. Today, TSMC is one of the world’s 10 most valuable listed companies, and it is critical to progress in smartphones, electric vehicles, AI and more. Only Samsung has been able to keep up with making the most advanced architectures, but it lags far behind in market share.

TSMC recently said it produces 99 per cent of the chips used to train artificial intelligence, known as AI accelerators or graphics processing units (GPUs).

“[That’s] about as close to the definition of monopoly as you can get,” says Miller.

“It's striking that some of the commentary from Wall Street was confusion about why TSMC hadn't hiked prices more. But TSMC's leadership would say they're not thinking about this contract or the next.

“They're thinking about relationships that have already lasted decades and that they hope will last decades into the future. That requires a level of trust in manufacturing and, I think, trust in pricing with their customers.”

From the Cold War to national priority

National interests have been central to the semiconductor industry’s evolution. Miller’s initial interest in semiconductors was sparked by “their central position in competition between countries for national power”.

Some of the US’s first commercially produced chips were used in nuclear missiles’ guidance systems during the Cold War against Russia. Today, China’s access to high-end technology preoccupies much of the US’s defence thinking.

China is the largest importer of semiconductors, spending more money each year on them than on oil over the past decade, and the US has been trying to limit its access to the most advanced technology.

“Both China and the US have identified artificial intelligence as… a general-purpose technology that each government believes will have broad economic, technological and strategic ramifications.

“Indeed, we already see both governments beginning to use AI, … to sift through intelligence that their spy satellites are collecting, … or to guide drones more accurately as they fly through the air.

"Everyone has access to algorithms that are largely open-sourced. Talent disperses widely across the world. But computing power is produced by a tiny number of companies.”

The US has prevented TSMC from building state-of-the-art chips for Chinese clients, including limiting sales to Chinese customers, such as Huawei.

“But that only underscores the extent to which TSMC is a company with unique capabilities that no one, in China or anywhere else, can match,” says Miller

ASML: betting on the long term

No country or company can do it alone, but one company may come close to being indispensable.

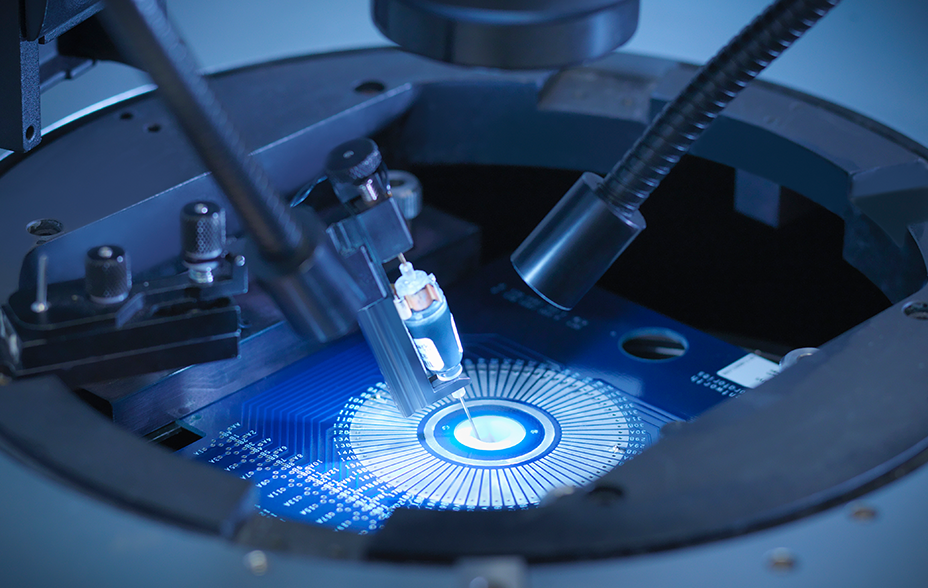

Today, the most complex chip-making tools are photolithography machines. The Dutch firm ASML produces the most advanced equipment capable of “carving the most intricate patterns in silicon.” It has a 100 per cent market share of the leading equipment and harnesses a complex supply chain to do so.

Miller puts its dominance down to management’s long-term mindset. In the 1990s and 2000s, the company made a strategic “bet on producing the next-generation [extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV)] tool that today is central for advanced chipmaking.”

The company persevered despite EUV being seen “as harder than bringing a man to the moon.”

According to Miller, the machines “require the flattest mirrors humans have ever made and one of the strongest lasers ever deployed in a commercial device”.

Inside every machine, “a tiny ball of tin is pulverised into a plasma. The temperature of this explosion is 40 times hotter than the sun's surface.

“Humans have made no tools more complex than these. You can understand why it seemed highly implausible for a long time that a machine with an explosion like this inside would be usable in a factory context.”

ASML succeeded. Its latest machines cost over $300m per machine and contain hundreds of thousands of components; each must be extraordinarily reliable and precise. Misplacing even a single atom can disrupt the process when manufacturing at the nanometre (billionths of a metre) scale.

Miller suggests it will be almost impossible for anyone to catch up with the company in the foreseeable future.

“By the time you’ve learned to replicate it, ASML will have already produced its next-generation tool, and so [its competitors] will still be behind.”

NVIDIA: all-in on GPUs

Miller views technology leadership as critical for establishing longevity: "Ultimately, the only way you’ve got a defensible market position is by having better technology than your competitors.”

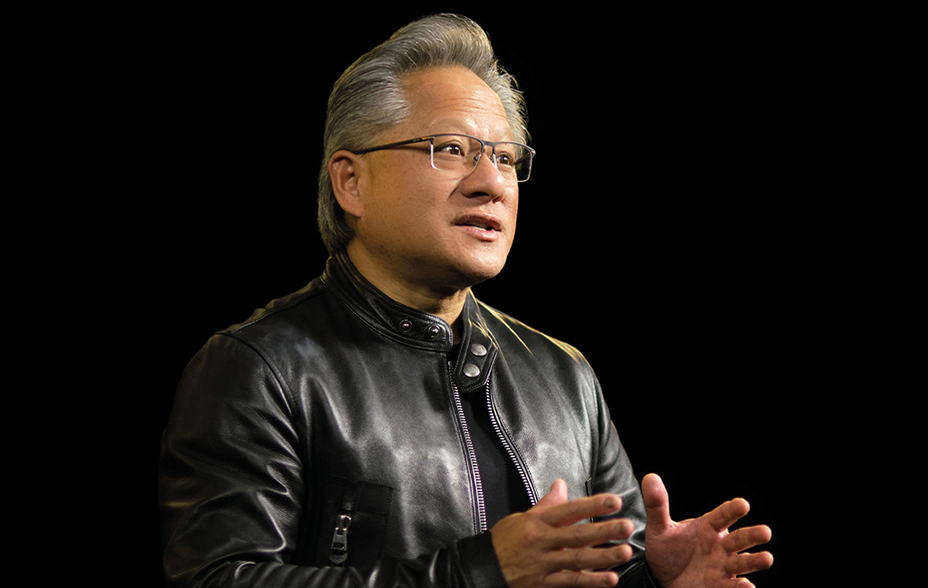

NVIDIA has done this through the foresight of its chief executive, Jensen Huang, who invested heavily in the developing technology and software now critical to AI models.

The first large-scale generative AI tool to capture widespread public attention was OpenAI’s generative AI chatbot, ChatGPT. About a month after Chip War’s publication, ChatGPT launched, and demand for NVIDIA's graphics chips soared as others rushed to build and train their own AI models.

But over a decade prior, Huang had realised his firm’s graphics processing unit (GPU) chips could be used for more than just rendering computer graphics. He understood that their parallel processing capabilities could be used to solve complex scientific problems and accelerate computational tasks.

His company invested deeply in building software tools called CUDA to make GPU programming more accessible to developers. When AI researchers adopted the technology, NVIDIA seized the opportunity, giving CUDA extra functionality and optimising the GPUs’ architectures to help.

At the time, AI was seen as “far out and implausible”, at least as a business for NVIDIA.

Miller highlights Wall Street’s discomfort on: “first, building chips for an industry that didn't exist, and second, giving away the software for free.”

Huang understood that repurposing NVIDIA’s chips would make them “vastly more efficient than the existing class of processors, called CPUs (central processing units)”.

“NVIDIA bet that if it could make its chips efficient for AI, it would drive down the costs of AI and, therefore, blow up in a much larger market than anyone else foresaw.”

Miller contrasts that with Intel, which was once the world’s largest chipmaker and still plays a dominant role in the design and manufacture of the CPUs that are still important for personal computing and data centres.

He points out that it “flirted” with AI in various formats but “could never really convince itself to dive in in a way that Jensen bet the company on AI being its future.

“He deserves much credit for NVIDIA's decisions,” says Miller of one of the Fortune 500’s longest-serving chief executives.

“Significant bets were taken, not based on short-term profit, but instead on long-term technological shifts that, it's now quite clear, NVIDIA bet correctly.”

Patience is a virtue

It’s a reminder that technology moves fast, but perhaps not as quickly or clearly, nor always in the same direction, as we might anticipate.

As Miller highlights, companies need to determine “the proper use case, the correct form factor and the suitable business model” and that can take decades.

He points out that it was a decade from the invention of the first transistor to the first integrated circuit. Then, it took another decade for mainframe computers to become widespread in large corporations. Two decades later came the first personal computer, and another couple of decades later, the first smartphone.

“Each of these steps was ‘transformative’ and produced companies that were among the most valuable in the world at the time,” Miller says, suggesting that AI still has a long road ahead.

"We have yet to conceptualise [its] application in many spheres because we’re in the very earliest stages of a technological shift that will take decades to play out.”

Progress will not be a straight line, but we can be confident that the advances in artificial intelligence and other emerging industries, such as space travel and the energy transition, will demand more advanced chip designs and complex chip manufacturing.

For that to happen, companies need access to capital from patient investors prepared to back visionary companies and leaders through the ups and downs of change. That is Scottish Mortgage’s forte.

Risk factors

The trust invests in overseas securities. Changes in the rates of exchange may also cause the value of your investment (and any income it may pay) to go down or up.

The Trust invests in emerging markets, which includes China, where difficulties with market volatility, political and economic instability including the risk of market shutdown, trading, liquidity, settlement, corporate governance, regulation, legislation and taxation could arise, resulting in a negative impact on the value of your investment.

About the author - Hamish Maxwell

Investment Specialist

Hamish joined Baillie Gifford in 2017 and is an investment specialist. He joined the Scottish Mortgage Team in 2024 and works closely with the managers, meeting with portfolio companies and conducting in-depth portfolio discussions with shareholders. Alongside this, he creates engaging content which makes the Scottish Mortgage portfolio accessible to all its shareholders. Prior to Scottish Mortgage, Hamish worked on Baillie Gifford's international equities strategies alongside Lawrence Burns. Before Baillie Gifford, Hamish served in the Royal Navy as a Commissioned Officer, including time as a leader in aircraft carriers, mine-hunters, and nuclear submarines. During training, he was awarded top-of-class by HRH Prince Edward. Hamish is a CFA Charterholder, and he achieved an MBA from City, University of London where he received the EU Award.

Regulatory Information

This content was produced and approved at the time stated and may not have been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of production and may not reflect current thinking. Read our Legal and regulatory information for further details.

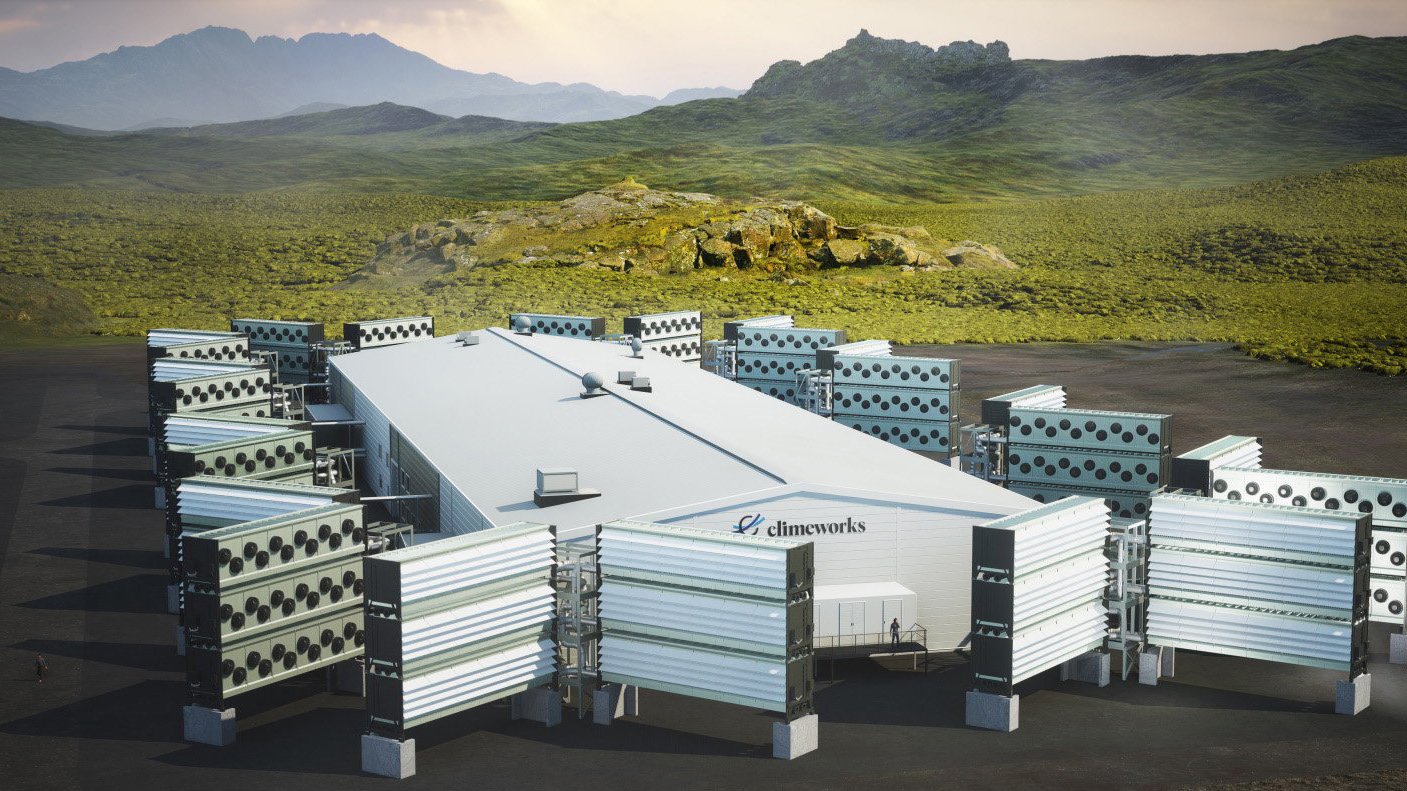

A Key Information Document is available by visiting our Documents page. Any images used in this content are for illustrative purposes only.

This content does not constitute, and is not subject to the protections afforded to, independent research. Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned. The views expressed are not statements of fact and should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment.

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed on the London Stock Exchange and are not authorised or regulated by the FCA.

Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 (BGA) holds a Type 1 licence from the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong to market and distribute Baillie Gifford’s range of collective investment schemes and closed-ended funds such as investment trusts to professional investors in Hong Kong.

Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited (BGAS) is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore as a holder of a capital markets services licence to conduct fund management activities for institutional investors and accredited investors in Singapore. BGA and BGAS are wholly owned subsidiaries of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, which is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co.

Europe

Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust PLC (the “Company”) is an alternative investment fund for the purpose of Directive 2011/61/EU (the “AIFM Directive”). Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is the alternative investment fund manager (“AIFM”) of the Company and has been authorised for marketing to Professional Investors in this jurisdiction.

This content is made available by Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (“BGE”), which has been engaged by the AIFM to carry out promotional activities relating to the Company. BGE is authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland as an AIFM under the AIFM Regulations and as a UCITS management company under the UCITS Regulation. BGE also has regulatory permissions to perform promotional, advisory and Individual Portfolio Management activities. BGE has passported its authorisations under the mechanisms set out in the AIFM Directive.

Belgium

The Company has not been and will not be registered with the Belgian Financial Services and Markets Authority (Autoriteit voor Financiële Diensten en Markten / Autorité des services et marchés financiers) (the FSMA) as a public foreign alternative collective investment scheme under Article 259 of the Belgian Law of 19 April 2014 on alternative collective investment institutions and their managers (the Law of 19 April 2014). The shares in the Company will be marketed in Belgium to professional investors within the meaning the Law of 19 April 2014 only. Any offering material relating to the offering has not been, and will not be, approved by the FSMA pursuant to the Belgian laws and regulations applicable to the public offering of securities. Accordingly, this offering as well as any documents and materials relating to the offering may not be advertised, offered or distributed in any other way, directly or indirectly, to any other person located and/or resident in Belgium other than to professional investors within the meaning the Law of 19 April 2014 and in circumstances which do not constitute an offer to the public pursuant to the Law of 19 April 2014. The shares offered by the Company shall not, whether directly or indirectly, be marketed, offered, sold, transferred or delivered in Belgium to any individual or legal entity other than to professional investors within the meaning the Law of 19 April 2014 or than to investors having a minimum investment of at least EUR 250,000 per investor.

Germany

The Trust has not offered or placed and will not offer or place or sell, directly or indirectly, units/shares to retail investors or semi-professional investors in Germany, i.e. investors which do not qualify as professional investors as defined in sec. 1 (19) no. 32 German Investment Code (Kapitalanlagegesetzbuch – KAGB) and has not distributed and will not distribute or cause to be distributed to such retail or semi-professional investor in Germany, this document or any other offering material relating to the units/shares of the Trust and that such offers, placements, sales and distributions have been and will be made in Germany only to professional investors within the meaning of sec. 1 (19) no. 32 German Investment Code (Kapitalanlagegesetzbuch – KAGB).

Luxembourg

Units/shares/interests of the Trust may only be offered or sold in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (Luxembourg) to professional investors within the meaning of Luxembourg act by the act of 12 July 2013 on alternative investment fund managers (the AIFM Act). This document does not constitute an offer, an invitation or a solicitation for any investment or subscription for the units/shares/interests of the Trust by retail investors in Luxembourg. Any person who is in possession of this document is hereby notified that no action has or will be taken that would allow a direct or indirect offering or placement of the units/shares/interests of the Trust to retail investors in Luxembourg.

Switzerland

The Trust has not been approved by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (“FINMA”) for offering to non-qualified investors pursuant to Art. 120 para. 1 of the Swiss Federal Act on Collective Investment Schemes of 23 June 2006, as amended (“CISA”). Accordingly, the interests in the Trust may only be offered or advertised, and this document may only be made available, in Switzerland to qualified investors within the meaning of CISA. Investors in the Trust do not benefit from the specific investor protection provided by CISA and the supervision by the FINMA in connection with the approval for offering.

Singapore

This content has not been registered as a prospectus with the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Accordingly, this content and any other content or material in connection with the offer or sale, or invitation for subscription or purchase, of the Trust may not be circulated or distributed, nor may be offered or sold, or be made the subject of an invitation for subscription or purchase, whether directly or indirectly, to persons in Singapore other than (i) to an institutional investor (as defined in Section 4A of the Securities and Futures Act 2001, as modified or amended from time to time (SFA)) pursuant to Section 274 of the SFA, (ii) to a relevant person (as defined in Section 275(2) of the SFA) pursuant to Section 275(1), or any person pursuant to Section 275(1A), and in accordance with the conditions specified in Section 275 of the SFA, or (iii) otherwise pursuant to, and in accordance with the conditions of, any other applicable provision of the SFA.

Where the Trust is subscribed or purchased under Section 275 by a relevant person which is:

(a) a corporation (which is not an accredited investor (as defined in Section 4A of the SFA)) the sole business of which is to hold investments and the entire share capital of which is owned by one or more individuals, each of whom is an accredited investor; or

(b) a trust (where the trustee is not an accredited investor) whose sole purpose is to hold investments and each beneficiary of the trust is an individual who is an accredited investor, securities or securities-based derivatives contracts (each term as defined in Section 2(1) of the SFA) of that corporation or the beneficiaries’ rights and interest (howsoever described) in that trust shall not be transferred within six months after that corporation or that trust has acquired the securities pursuant to an offer made under Section 275 except:

(1) to an institutional investor or to a relevant person or to any person arising from an offer referred to in Section 275(1A) or Section 276(4)(c)(ii) of the SFA,

(2) where no consideration is or will be given for the transfer;

(3) where the transfer is by operation of law; or

(4) pursuant to Section 276(7) of the SFA or Regulation 37A of the Securities and Futures (Offers of Investments) (Securities and Securities-based Derivatives Contracts) Regulations 2018.