Scottish Mortgage deputy manager review

Lawrence Burns – Deputy manager, Scottish Mortgage

- Despite the rapid advances in AI, its impact is still early days as companies find ways to leverage and apply the technology

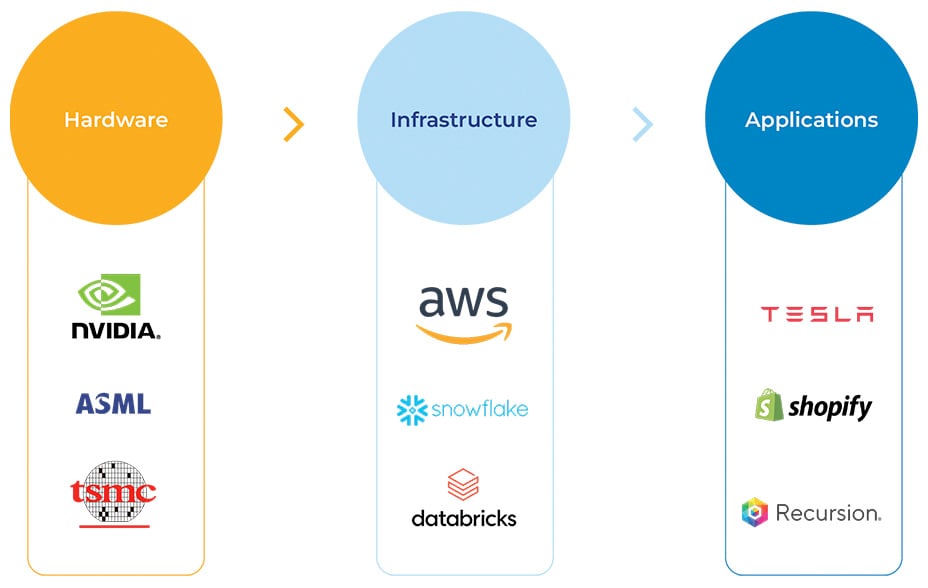

- Scottish Mortgage’s AI holdings span hardware, infrastructure and applications

- Scottish Mortgage invests in and supports transformative change. The developments in AI demonstrate that progress is continuing at pace

As with any investment, your capital is at risk.

In the summer of 2018, I was fortunate to spend two full days in Palo Alto talking with Professor Brian Arthur, one of the world’s most influential thinkers on technology and the economy. He told me he thought artificial intelligence (AI) would be the most significant invention since the Gutenberg printing press.

It was quite a statement, given that the printing press was invented over half a millennium ago. Before its invention, scribes painstakingly copied books by hand. Most were kept in monasteries chained to desks to prevent theft. Gutenberg’s invention made knowledge accessible, allowing ideas to spread like never before. It powered the Scientific Revolution, the Reformation, and countless political revolutions. Its impact was profound and immeasurable.

AI has the potential to impact the world similarly, but instead of externalising information, it is externalising intelligence. Making it available at rapidly decreasing cost anywhere in the world, instantly and on demand. That could be to write a high school student’s essay on the reign of Queen Victoria or to help a radiologist identify a cancerous tumour.

Given that you can do even more with intelligence than you can with information, Prof Brian Arthur concluded that, logically, AI’s impact should be even more significant than the printing press. Fast-forward nearly six years, and his views look increasingly prescient. The latest AI models now very nearly match or exceed human performance in a growing number of tasks, including image classification, reading comprehension, visual reasoning and competition-level mathematics.

The progress in surpassing human performance benchmarks has been so fast that the editor-in-chief of the AI Index recently commented that a decade ago, benchmarks would serve the AI community for five-to-ten years, but now they often become irrelevant in just a few years.

This pace of progress has been made possible by the continued exponential improvement of the three inputs that drive AI performance: compute, data and algorithms. A way of measuring these improvements is the number of parameters a model has. Each parameter is a variable that the model can adjust during the training to better predict outcomes.

In 2018, when talking to Prof Arthur, GPT-1 had just been released, and it had 100 million parameters. Earlier this year, OpenAI released GPT-4, which is believed to have 1.7tn parameters, demonstrating the rapid change in model size and complexity in just a few years.

When considering investment opportunities within artificial intelligence, it can be helpful to divide them into three layers: hardware, infrastructure, and applications. Scottish Mortgage is invested in companies involved in each of these layers.

The layers of artificial intelligence

Hardware

The hardware layer is about making the physical computational devices that enable AI. In this layer, since 2016, we have owned NVIDIA, the leading designer of AI chips. The company has a dominant position, with 90 per cent of all generative AI models trained on its chips. It is the critical enabler of AI.

However, NVIDIA only designs its chips, it needs others to fabricate them. For this, it uses TSMC, the world’s largest integrated circuit manufacturer and a recent addition to the Scottish Mortgage portfolio.

It has a dominant position in an industry where scale matters with the latest foundries, such as the three it is building in Arizona, costing over $65bn. These chip foundries are so critical to supply chains and the economy that they hold geopolitical significance. Consequently, the US government is providing over $10bn in federal grants and loans to ensure they are built in the US.

TSMC can be thought of as a royalty on global computing power, just as NVIDIA can be thought of as a royalty on artificial intelligence. To help make chips, TSMC requires a particularly crucial piece of equipment: lithography machines.

For these, it relies on another of our longstanding holdings, ASML, which has a monopoly position in advanced lithography machines. These rely on the world’s flattest mirrors and one of the most powerful commercial lasers to create an explosion 40 times hotter than the surface of the sun to pattern tiny shapes on silicon that measure just a few nanometres.

This precision is what allows chips to be made containing tens of billions of transistors. To different extents, all three of these hardware companies benefit from the rise of AI while possessing dominant and near-impregnable competitive positions.

The founder of OpenAI, Sam Altman is understandably evangelistic and has gone as far as to say that computing power may become the most precious commodity in the world. This is because the demand for computing power and intelligence could be effectively limitless with demand progressively unlocked by supply at ever lower price points.

Crucially we are seeing a situation where the cost to serve continues to rapidly fall leading these three hardware companies to face a large structural opportunity even if it will likely remain a bumpy cyclical journey along the way.

Infrastructure

The next layer is infrastructure. Here, we have the cloud service providers that buy NVIDIA’s chips and offer scalable, on-demand access allowing companies to train and deploy AI models without the overhead of building their own infrastructure.

In essence, the cloud service providers democratise access to both computing and AI. There are three dominant cloud service providers. We own Amazon, which operates Amazon Web Services, the largest cloud service provider in the world.

There are also companies that are building large foundational models for AI. Foundational models are trained on broad datasets (ie large swathes of the internet) that can be used to perform a wide variety of tasks. They are also commonly used as the base upon which to build more specialised AI models. These foundational models have become so large and complex that the computing power and energy required to train them is making them increasingly expensive.

The foundational models expected to be released later this year will likely have cost close to $1bn to be trained. That cost is expected to rise to between $5bn and $10bn for the latest models in 2025 and 2026, which is indicative of the growing demand for hardware companies.

A consequence of this is that the ability to create such models is fast becoming the preserve of just a handful of mega-scale companies and those receiving their patronage. We have several holdings developing foundational models, such as Meta Platforms, Amazon and NVIDIA.

The developments in AI provide robust evidence that progress is continuing at pace.

Another set of companies providing the infrastructure for AI are database companies. The explosion of data in the world has meant that more data will be created in the next three years than was created in the last thirty years.

Companies that Scottish Mortgage owns, such as Databricks and Snowflake, help businesses store, manage, and use that data in the cloud. That same data is also the lifeblood of AI, with companies increasingly looking to feed their data into foundational models, allowing the creation of powerful new applications specific to their business.

For example, commerce software giant Shopify has combined its proprietary data and merchants’ data with OpenAI’s GPT to create what it calls Sidekick, a conversational assistant that merchants can talk to and ask questions about how to use Shopify’s platform. It can even be asked to accomplish specific tasks, such as compiling reports on bestselling products. AI will allow companies to do more with their data and, in doing so, increase the value of those that offer tools to store, parse and effectively use data.

Applications

The final layer is the application layer. This is about making productive use of AI in the real world. A significant number of Scottish Mortgage’s holdings are making use of it to expand addressable markets, reduce costs and dig deeper competitive moats.

Tesla is using AI to make its cars self-driving and even hopes to leverage those advances to produce humanoid robots. After all, what is a self-driving car if not a robot operating in the physical world? Demonstrative of its progress is that Tesla cars have now driven 1.3bn miles autonomously, and the company is already in conversation with another major carmaker about licensing its self-driving technology.

Recursion Pharmaceuticals is leveraging AI to improve drug discovery by creating a map of human biology that could dramatically cut the cost of developing new drugs. Tempus Labs has built a vast database of over 7 million cancer patients’ clinical records and is applying machine learning to that dataset to enable physicians to make better treatment decisions.

Meta Platforms is using AI to improve advertising targeting across its platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp to powerful effect. Spotify is using it to enhance its personalised song recommendations and has released its AI-powered DJ to much fanfare. AI also enables podcasts on Spotify to be translated into other languages using the actual voice of the podcaster.

The impact of AI across the portfolio is vast because all companies can benefit from the application of intelligence. AI can be thought of as a powerful new set of tools for companies to apply to their business that will, crucially, only get significantly better with time.

The companies that will be best placed to use this toolkit will be those with large amounts of proprietary data, software expertise and a culture of innovation. In each of these dimensions, our portfolio companies should be well-placed.

The opportunities of the application layer in new technology paradigms naturally lag behind those in the hardware and infrastructure layer. Those initial two layers need to scale first in order to support the development of applications. It can also take time and human ingenuity to find ways to leverage and apply powerful new technologies.

We can draw an analogy with the smartphone. When the iPhone was released, it was clearly an impactful piece of hardware. Still, it took time for companies and aspiring founders to build applications to utilise the new device’s potential fully. At its release in 2007, it would have been hard to immediately predict the new business models it would go on to enable, such as ride-hailing, food delivery, mobile payments and short-form video apps such as ByteDance’s TikTok. It even took time to appreciate just how meaningful it would be for existing digital activities such as ecommerce, streaming, and social media, which saw their market opportunities greatly enlarged.

Over time, the benefits of AI are likely to similarly expand to a greater number of companies and lead to new business models. After all, there is no point in investing billions in hardware and infrastructure if there are not a lot of applications to be built.

Conclusion

Despite the excitement surrounding AI, it is still important to remember that progress is rarely a straight line. We cannot rule out that there could be a period of digestion following heavy investments in the hardware and infrastructure layer as companies take longer than expected to work out how to use new capabilities.

Alternatively, we could encounter unexpected limitations to AI models requiring new algorithmic breakthroughs to be made. We are cognisant that the hardware companies, in particular, though currently propelled by insatiable demand, can be viciously cyclical businesses should they hit air pockets of demand.

We continue to expect them to perform well but, partially in recognition of this cyclicality, have been making some mild reductions. This has been the case for our largest holding, NVIDIA, following exceptionally strong performance and having grown its net income by over 500 per cent last year.

Overall, we still believe we are early in experiencing the impact of artificial intelligence. That impact has been most strongly felt in the hardware and infrastructure layers, but it should gradually expand to the application layer. The role of Scottish Mortgage will continue to be to invest in and support progress, and the developments in AI provide robust evidence that progress is continuing at pace.

On behalf of our shareholders, we invest in transformative change. We’re greatly encouraged by the founders of our portfolio companies telling us that, to them, the pace and magnitude of technological-driven change has never appeared greater. The possibility of such change is a crucial enabler of the outlier outcomes we seek, and aim to deliver for our shareholders.

Annual Past Performance To 31 March each year (net%)

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust plc | 12.7 | 99.0 | -9.5 | -33.6 | 32.5 |

Source: Morningstar, share price, total return, sterling.

Risk factors

The trust invests in overseas securities. Changes in the rates of exchange may also cause the value of your investment (and any income it may pay) to go down or up.

Unlisted investments such as private companies, in which the Trust has a significant investment, can increase risk. These assets may be more difficult to sell, so changes in their prices may be greater.

The Trust invests in emerging markets, which includes China, where difficulties with market volatility, political and economic instability including the risk of market shutdown, trading, liquidity, settlement, corporate governance, regulation, legislation and taxation could arise, resulting in a negative impact on the value of your investment.

About the author - Lawrence Burns

Deputy manager, Scottish Mortgage

Lawrence Burns was appointed deputy manager of Scottish Mortgage in 2021. He joined Baillie Gifford in 2009 and became a partner of the firm in 2020. During his time at the firm, his investment interest has become focused on transformative growth companies. He has been a member of the International Growth Portfolio Construction Group since October 2012 and in 2020 became a manager of Vanguard’s International Growth Fund. Lawrence is also co-manager of the International Concentrated Growth and Global Outliers strategies. Prior to this, he also worked in both the Emerging Markets and UK Equity teams. Lawrence graduated BA in Geography from the University of Cambridge in 2009.

Regulatory Information

This content was produced and approved at the time stated and may not have been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of production and may not reflect current thinking. Read our Legal and regulatory information for further details.

A Key Information Document is available by visiting our Documents page. Any images used in this content are for illustrative purposes only.

This content does not constitute, and is not subject to the protections afforded to, independent research. Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned. The views expressed are not statements of fact and should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment.

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed on the London Stock Exchange and are not authorised or regulated by the FCA.

Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 (BGA) holds a Type 1 licence from the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong to market and distribute Baillie Gifford’s range of collective investment schemes and closed-ended funds such as investment trusts to professional investors in Hong Kong.

Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited (BGAS) is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore as a holder of a capital markets services licence to conduct fund management activities for institutional investors and accredited investors in Singapore. BGA and BGAS are wholly owned subsidiaries of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, which is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co.

Europe

Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust PLC (the “Company”) is an alternative investment fund for the purpose of Directive 2011/61/EU (the “AIFM Directive”). Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is the alternative investment fund manager (“AIFM”) of the Company and has been authorised for marketing to Professional Investors in this jurisdiction.

This content is made available by Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (“BGE”), which has been engaged by the AIFM to carry out promotional activities relating to the Company. BGE is authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland as an AIFM under the AIFM Regulations and as a UCITS management company under the UCITS Regulation. BGE also has regulatory permissions to perform promotional, advisory and Individual Portfolio Management activities. BGE has passported its authorisations under the mechanisms set out in the AIFM Directive.

Belgium

The Company has not been and will not be registered with the Belgian Financial Services and Markets Authority (Autoriteit voor Financiële Diensten en Markten / Autorité des services et marchés financiers) (the FSMA) as a public foreign alternative collective investment scheme under Article 259 of the Belgian Law of 19 April 2014 on alternative collective investment institutions and their managers (the Law of 19 April 2014). The shares in the Company will be marketed in Belgium to professional investors within the meaning the Law of 19 April 2014 only. Any offering material relating to the offering has not been, and will not be, approved by the FSMA pursuant to the Belgian laws and regulations applicable to the public offering of securities. Accordingly, this offering as well as any documents and materials relating to the offering may not be advertised, offered or distributed in any other way, directly or indirectly, to any other person located and/or resident in Belgium other than to professional investors within the meaning the Law of 19 April 2014 and in circumstances which do not constitute an offer to the public pursuant to the Law of 19 April 2014. The shares offered by the Company shall not, whether directly or indirectly, be marketed, offered, sold, transferred or delivered in Belgium to any individual or legal entity other than to professional investors within the meaning the Law of 19 April 2014 or than to investors having a minimum investment of at least EUR 250,000 per investor.

Germany

The Trust has not offered or placed and will not offer or place or sell, directly or indirectly, units/shares to retail investors or semi-professional investors in Germany, i.e. investors which do not qualify as professional investors as defined in sec. 1 (19) no. 32 German Investment Code (Kapitalanlagegesetzbuch – KAGB) and has not distributed and will not distribute or cause to be distributed to such retail or semi-professional investor in Germany, this document or any other offering material relating to the units/shares of the Trust and that such offers, placements, sales and distributions have been and will be made in Germany only to professional investors within the meaning of sec. 1 (19) no. 32 German Investment Code (Kapitalanlagegesetzbuch – KAGB).

Luxembourg

Units/shares/interests of the Trust may only be offered or sold in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (Luxembourg) to professional investors within the meaning of Luxembourg act by the act of 12 July 2013 on alternative investment fund managers (the AIFM Act). This document does not constitute an offer, an invitation or a solicitation for any investment or subscription for the units/shares/interests of the Trust by retail investors in Luxembourg. Any person who is in possession of this document is hereby notified that no action has or will be taken that would allow a direct or indirect offering or placement of the units/shares/interests of the Trust to retail investors in Luxembourg.

Switzerland

The Trust has not been approved by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (“FINMA”) for offering to non-qualified investors pursuant to Art. 120 para. 1 of the Swiss Federal Act on Collective Investment Schemes of 23 June 2006, as amended (“CISA”). Accordingly, the interests in the Trust may only be offered or advertised, and this document may only be made available, in Switzerland to qualified investors within the meaning of CISA. Investors in the Trust do not benefit from the specific investor protection provided by CISA and the supervision by the FINMA in connection with the approval for offering.

Singapore

This content has not been registered as a prospectus with the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Accordingly, this content and any other content or material in connection with the offer or sale, or invitation for subscription or purchase, of the Trust may not be circulated or distributed, nor may be offered or sold, or be made the subject of an invitation for subscription or purchase, whether directly or indirectly, to persons in Singapore other than (i) to an institutional investor (as defined in Section 4A of the Securities and Futures Act 2001, as modified or amended from time to time (SFA)) pursuant to Section 274 of the SFA, (ii) to a relevant person (as defined in Section 275(2) of the SFA) pursuant to Section 275(1), or any person pursuant to Section 275(1A), and in accordance with the conditions specified in Section 275 of the SFA, or (iii) otherwise pursuant to, and in accordance with the conditions of, any other applicable provision of the SFA.

Where the Trust is subscribed or purchased under Section 275 by a relevant person which is:

(a) a corporation (which is not an accredited investor (as defined in Section 4A of the SFA)) the sole business of which is to hold investments and the entire share capital of which is owned by one or more individuals, each of whom is an accredited investor; or

(b) a trust (where the trustee is not an accredited investor) whose sole purpose is to hold investments and each beneficiary of the trust is an individual who is an accredited investor, securities or securities-based derivatives contracts (each term as defined in Section 2(1) of the SFA) of that corporation or the beneficiaries’ rights and interest (howsoever described) in that trust shall not be transferred within six months after that corporation or that trust has acquired the securities pursuant to an offer made under Section 275 except:

(1) to an institutional investor or to a relevant person or to any person arising from an offer referred to in Section 275(1A) or Section 276(4)(c)(ii) of the SFA,

(2) where no consideration is or will be given for the transfer;

(3) where the transfer is by operation of law; or

(4) pursuant to Section 276(7) of the SFA or Regulation 37A of the Securities and Futures (Offers of Investments) (Securities and Securities-based Derivatives Contracts) Regulations 2018.